Romeo + Juliet

PRG supported the Broadway revival of Romeo + Juliet, providing lighting and sound for this reimagined classic.

Swept Away, the much-talked-about musical that opened at the Longacre Theatre in November, is based on the album, Mignonette by American folk-rock band The Avett Brothers. The story, which was inspired by the true story of the shipwreck of a British yacht in 1884, follows four sailors stranded at sea for nearly three weeks and the moral dilemma they ultimately face. The ninety-minute production premiered at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre in 2022 and moved to Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., before reaching Broadway.

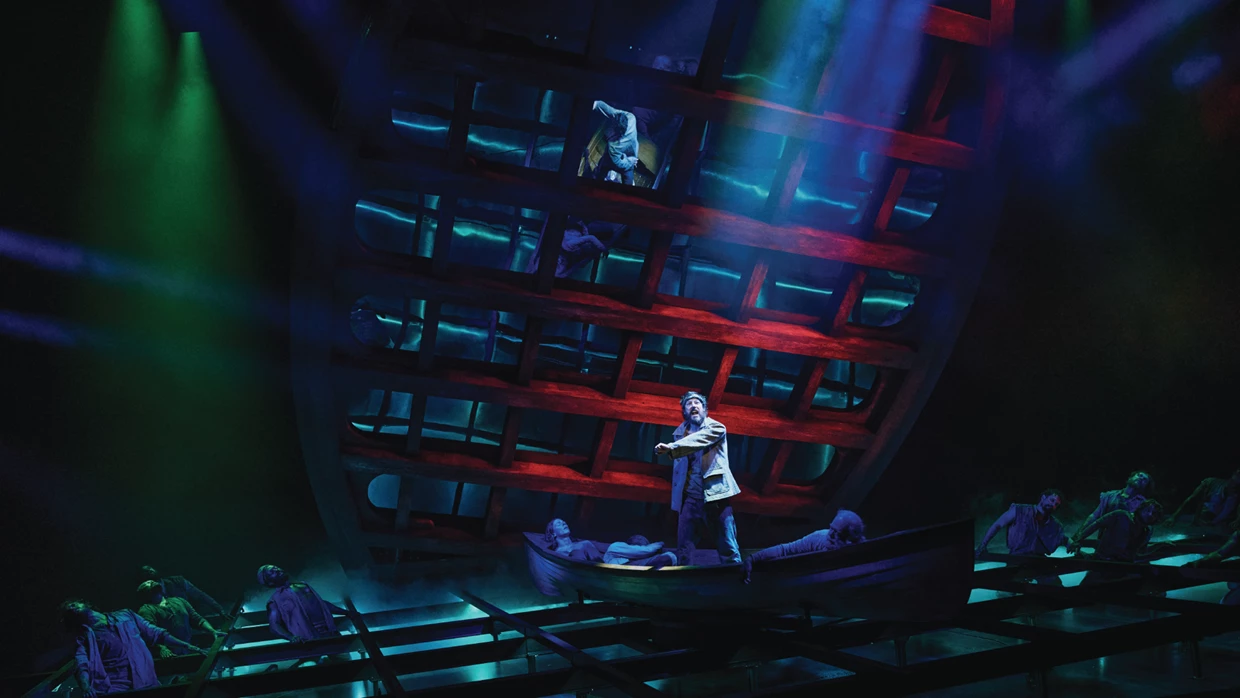

PRG is proud to have provided lighting, scenic and automation to this emotionally charged production which left audiences blown away by its jaw-dropping lighting design by Tony Award Winner (Spring Awakening) Kevin Adams and scenic design by Tony Award Winner (Hadestown) Rachel Hauck. The New York Times recognized the shipwreck as one of the “9 Best Theater Moments of 2024," with critics saying, "Winds blow, timbers shiver, and the ship tilts at a thrilling, impossible angle. Disaster never looked so good."

“Swept Away’s Director, Michael Mayer and I went to see Billy Budd at the Met in 2012, and when we started work on this show, I kept telling Michael that Swept Away should look like that production of Billy Budd. That way it would be lit like an old-fashioned incandescent-era opera with gel and a narrow palette and that it would have a black void surround. Those design elements would separate Swept Away from the conventional look of Broadway musicals while supporting the show's extremely dark tone," said Adams.

For the show's first half, which takes place on a big whaling ship, the lighting plot is wildly asymmetrical, laid out around a complicated off-center rig of ropes and rigging for the ship. There is a strong axis of sunlight that runs stage right of the centerline of the ship and a second axis of moonlight from farther stage left. For these, Adams used “old school” conventional fixtures, Par 64’s, ETC Source 4 Pars and S4 Lekos, with individual gels, no scrollers. To light the actors, he used Martin Mac Ultra and Mac One, both of which are bright, quiet and look great on human skin.

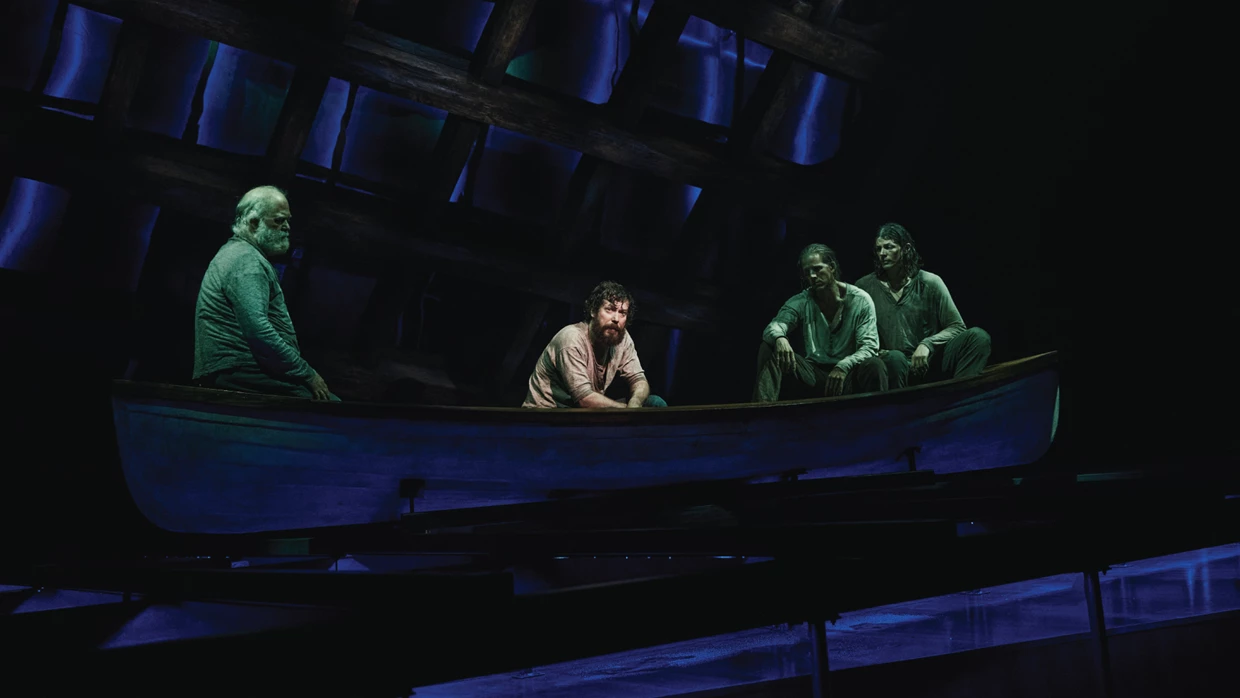

The show's second half takes place after the shipwreck and finds the four remaining actors adrift at sea in a small lifeboat. Here, the music and scenes get a little more expressionistic and the colors become more saturated. The sunny day becomes a harsh golden yellow and the nights turn to monochromatic blues and greens.

“We used LightStrike software to allow the lighting fixtures to follow the actors in the small lifeboat using positioning information provided by the scenic automation system,” explained Adams. “We have four fixtures high left and right that are dedicated to each performer, and at times, we add a flatter box-boom mover to fill in a face for a specific character."

The small boat is surrounded by a sea of unseen LED pixel tape that points at the deck and creates different atmospheres of moving water around the boat. PRG’s Mbox® media server was used to individually control over 10,000 pixels in the LED pixel tape. “It’s a field to make saturated moving color and gives the second half of the show a different tonal look from the big ship of the of the first half. I like how the LED ocean isolates the boat when seen through the mirrors hanging above it,” said Adams.

“PRG was key in making my lighting and special effects work. I’ve worked with them for 25 years, and it was no surprise that they could provide a rig of quiet movers and make it affordable. They did a terrific job," said Adams.

While researching the show, Adams, Hauck and costume designer Susan Hilferty visited a maritime museum in Mystic, Connecticut, whose artifacts include a collection of 19th-century ship photographs and paintings and the last American whaling ship, built in1840. Said Hauck, “The research we did truly paid off, we understood how those boats feel. The incredible scenic work by Scenic Art Studios resulted in what looked like a real, rugged, truly weathered ship out for its last sail. We combined aging techniques to achieve this, which added real depth and character to the whaling ship. With Kevin’s lights, it really does look like an oil painting."

One of the challenges in building the big ship was how practical and robust it had to be. “I didn't realize how aggressively David Neumann, the show's choreographer, would use every inch of the ship and put all kinds of lateral force on the structure. In the first production, the cast kept breaking bits of the ship with the muscular choreography,” said Hauck. "So, we continued to strengthen the boat and structure to support the choreography, and then we built the Broadway boat to be much stronger.”

The ropes, tensioned up to 400 lbs. to support the performers’ weight, are attached to a grid secured to the building 35 ft over the stage (above the lighting). They’re on a kabuki release mechanism to quickly drop to facilitate the scene shift from the sizeable whaling ship to the small lifeboat.

At the moment of the shipwreck, through choreography and technology, the actors use the release of these lines to weave a compelling and frightening narrative in slow motion. After the ship sinks, it has no connection to the grid except for four lines lifting it. The downstage edge rises up, and the bottom becomes a backdrop that hovers in the air over the lifeboat which floats in the middle of the stage deck, completely adrift.

”The shipwreck is a huge tonal transition between the big whaler full of life to a tiny, isolated lifeboat lost in the middle of a giant ocean. The audience can see that that those guys are in huge trouble. There's just nothing else around but water,” Hauck observed. “The structure of the big boat looming over them becomes the memory that haunts them.”

The canoe-like lifeboat an actual wooden boat the production purchased for the show, is held above an “ocean of steel” by just a cradle on a lift, reinforcing the feeling of being hopelessly isolated. Throughout these scenes it can remain stationary or, through the use of a “turtle”, rotate 360 degrees at variable speeds. The slow spin leaves the boat feeling like its adrift while offering the audience a changing view into the small space.

Hauck described the execution of the production, saying, “Needless to say, this design posed a series of incredibly complex engineering problems. I can’t say enough about the dedication and skill of the engineers at PRG and the team who built the show. They executed the mechanics of this beautiful heartbreaking show flawlessly. They did a brilliant job.”

Swept Away played its last performance at the Longacre Theater on December 29, 2024.